Which site would you like to visit?

By clicking the retail or wholesale site button and/or using rarewineco.com you are choosing to accept our use of cookies to provide you the best possible web experience.

You always know you're looking at the the sweet spot of the famed slope of Côte Brune by the small red roofed pavillon now owned by René Rostaing. The Guigal mural at far left marks La Turque while the larger pavillon at top marks the holdings of Domaine Barge.

Over the past two decades, the world has learned a lot about what makes great wines.

Bordeaux’s Garagiste Movement confirmed that technical winemaking and low yields do not compensate for young vines or a mediocre site. And the iconization of Burgundy and Barolo reminds us that the world’s greatest wines are born of great terroirs and traditionally inspired winemaking.

Few places on Earth have benefited more from this heightened awareness than Côte Rôtie, one of the most noble sites of all. Despite being revered for more than 2000 years, Côte Rôtie nearly disappeared in the twentieth century, as its vineyards were abandoned. Only recently has it again enjoyed a level of appreciation commensurate with the singular grandeur of its wine.

“Côte Rôtie is, after all, one of the world’s very few wines whose depth of character and history make it utterly irreplaceable.”

This reversal of fortune is important to those of who place a high value on wines of true individuality. Côte Rôtie is, after all, one of the world’s very few wines whose depth of character and history make it utterly irreplaceable.

During the next few weeks, we will be paying tribute to Côte Rôtie’s greatness with this special issue of The Rare Wine Co. newsletter. With each offer, we will feature one of the small number of traditionally inspired vignerons whose wines we consider essential to understanding Côte Rôtie’s beauty. We will tell the domaine’s story and will feature both young and old vintages.

You are likely to recognize some names, but perhaps not others. But each represents a true expression of what sets Côte Rôtie apart from every other expression of Syrah.

In the words of John Livingstone-Learmonth, “Côte Rôtie is the bridge between Burgundy and the Rhône.” Hermitage may be more famous and the grands crus of the Côte d’Or may produce more iconic wines. But only Côte Rôtie captures the best of both: the power and opulence of the south and the delicacy and nuance of the north.

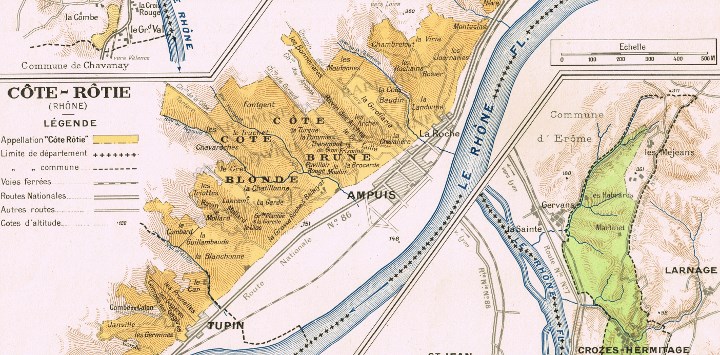

Côte Rôtie lies on the west bank of the Rhône River, centered above the market town of Ampuis. The appellation is nearly six miles in length. Yet because it is limited to the rugged, terraced slopes lining the Rhône—often at a dizzying 60-degree angle to the river below—a mere 300 hectares of vineyards are possible in the entire appellation.

A circa 1940s postcard. Note just how much of Côte Rôtie’s slopes were en friche—overgrown by trees and bushes. The back-breaking work of clearing it, and planting new vines in the rocks, took years.

Yet, as recently as the late 1950s, less than 20% of Côte Rôtie’s land had grapevines. Because of the challenges posed by growing grapes here, most of the local families had abandoned their vineyards. Instead, they survived by growing vegetables or went to work in nearby factories.

Côte Rôtie’s resurrection didn’t begin in earnest for another thirty years. Behind it were a number of factors, including a new growers’ organization led by Albert Dervieux; the commercial success of the 1976 vintage; new roads up the slopes; Guigal’s rising fame; support from Robert Parker; and, finally, a series of four consecutive great harvests between 1988 and 1991.

50 years ago, all Côte Rôties were blends of lieux-dits. Here a circa 1940s Larmat Map shows 60+ parcels, many of which were only partially planted. Click Here to open larger, zoomable map in a new tab.

Though ancient in its origin, the name Côte Rôtie—roasted slope—is misleading, as it suggests wines baked by the sun and possessing high degrees of alcohol.

In fact, Côte Rôties are, by their nature, wines of remarkable finesse and lower in alcohol than Hermitage. Hugh Johnson has said of Hermitage and Côte Rôtie: “Of the two, Côte Rôtie has the more fragrant memories, of bottles that grew so fine and delicate with age that they could have had Margaux in their vines.”

In the past, Côte Rôties were about 12% alcohol. But even today, the classic examples are not much more than 13%. The wines’ delicacy is sometimes augmented by the presence of some Viognier in the vineyards. When harvested and co-fermented with Syrah, Viognier is allowed to make up to one-fifth of the blend. But in practice it seldom makes up more than 2 or 3% and sometimes none at all.

The appellation is divided among dozens of sites, or lieux-dits—some famous and some not. The soils change as you go from north to south. The northern half of the appellation tends to be darker, iron-rich schist, while the more southern soils are a mixture of pale granite and schist. These soils have a profound effect on the character of the wines.

The northern lieux-dits like Côte Brune (and the famed sub-parcel la Turque), La Landonne, Rozier, Viallière and Grandes Places tend to produce more tannic, slow-to-mature Côte Rôties. The great central sites—like Côte Blonde and La Mouline—produce wines of more pronounced delicacy and elegance.

Today, the emphasis is on site-specific Côte Rôties, a trend begun in the 1960s by Guigal. But 50 years ago, all Côte Rôties were blends of lieux-dits. Even the “Côte Brunes” of Marius Gentaz were never 100% Côte Brune—much as the “Barolo Cannubi” of Bartolo Mascarello’s father was never 100% Cannubi.

Today, few domaines put their blended Côte Rôtie front and center, as their flagship wine. Principally among these are Jamet, Bernard Burgaud and Jasmin.

“Having tasted 2012s at nearly twenty different domaines, we came away convinced that the vintage is a true gift, with depth, elegance and harmony that comes along rarely...”

Looking back over the past thirty years, it is impossible to characterize the “perfect” Côte Rôtie vintage, since magic is produced under a variety of conditions. There’s no doubt that the ripe, powerful years of 1989, 1990, 1999, 2009 and 2010 produced some monumental wines. But are they any greater than the magical wines made in more elegant years like 1969, 1985, 1988 and 1991—all of which are equally glorious?

Of course not, and in fact a strong case can be made that the latter group are the quintessential Côte Rôtie years, emphasizing perfume and finesse over power. And we have a new vintage to add to this list: 2012. Having tasted 2012s at nearly twenty different domaines, we came away convinced that the vintage is a true gift, a vintage of depth, elegance and harmony that comes along rarely, particularly in these times of warm northern Rhône growing seasons.

Considering all the conditions that can distinguish Côte Rôtie from all the other winegrowing regions of the world, 2012 is an ideal Côte Rôtie vintage. It is that rare year that, in its subtlety, refinement, nuance and, above all, expression of terroir, truly captures Côte Rôtie’s soul.

We’re further convinced that it’s a vintage in which classically inspired domaines made wines whose great quality will continue to unfold over many years, reminding everyone who cares to taste with an open mind, that this is where Côte Rôtie’s greatness lies: in grace and sensuality, not in power and weight.

While the featured vintage here is 2012, this offer is far more than that, of course. It is the culmination of many years of visits to Côte Rôtie, interviews with growers, tastings and historical research. It also represents years of painstaking work in acquiring the wines you see here.

The increasing difficulty of finding well-stored classic Côte Rôtie makes it even more important than in the past to establish your own collection, by buying younger vintages while they still represent incredible value.

Offers like this are bittersweet. On the one hand, it gives us great pleasure to share our love of Côte Rôtie and, hopefully, to excite passion for these unique and wonderful wines. But we’re always sad to see the wines that we’ve collected over so many years leave our care, possibly never to be replaced.

This last comment bears noting. As the appreciation of classically made Northern Rhône reds has increased, our ability to come up with treasures like these has been sharply diminished. In our article on Jamet, for example, we note that years ago we regularly received cases of Côte Brune when we thought we were getting the normal Côte Rôtie. It wasn’t that our suppliers shipped us the wrong box. In fact, those in the wine trade placed no greater value on the Côte Brune and in fact didn’t even recognize that it was a different wine.

Today, even the older wines of less-well known producers like Burgaud and Champet have become more elusive, as their intrinsic value becomes more appreciated. And don’t expect to find much old wine in the growers’ cellars. Few of these small producers had the means (or the incentive at the time) to maintain a library of old vintages.

One of the few who kept a small one was Gilles Barge, who generously opened his vinothèque to us for this offer. Yet, we recognize that this will probably prove to be a once-in-a-lifetime opportunity to acquire so many great wines directly from his domaine.

If you’ve bought much old wine from us, or have attended any of our tastings, you know of the extraordinary condition of our old bottles. Whether acquired directly from the producer—or from a private cellar in Europe—each bottle we offer promises to deliver an exceptional drinking experience. And it’s rare that they don’t deliver on that promise.

As the following for classically made Côte Rôtie grows, it is becoming harder and harder to acquire older vintages at fair prices. The increasing difficulty of finding well-stored classic Côte Rôtie makes it even more important than in the past to establish your own collection, by buying younger vintages while they still represent incredible value.

With time, and if properly cellared, they will surely evolve into small masterpieces, comparable to the greatest Côte Rôties of the past.

The greatness of Côte Rôtie has been understood since Roman times, when Pliny the Younger praised Côte Rôtie’s violet bouquet, a quality modern wine lovers continue to revere.

In fact, with a worldwide reputation, and nearly 95% of the possible appellation under vine, it’s hard to imagine that there were ever dark days here.

Yet, Côte Rôtie nearly disappeared in the early 20th century. It had been pummeled by Phylloxera, two world wars and a global economic depression. Other wine regions suffered, but Côte Rôtie nearly perished, as the extreme steepness of its rocky slopes made it uneconomical to make wine here.

Farmers packing up apricots for transport. By 1945 a kilo of apricots, at one franc, was worth more than twice as much as a kilo of Côte Rôtie grapes

The decline began just after 1900. In the wake of Phylloxera, vineyards began to be abandoned, and young men left for nearby cities and jobs in factories. But there were holdouts.

Nine growers, including Jasmin and Vidal-Fleury, presented their wines at the 1909 Concours Agricole in Paris. Most of the remaining growers sold their fruit to big merchants either in nearby Ampuis, or in Burgundy. But a few growers, like Jean Dervieux and Jules Barge, took the bold step of domaine bottling, on a very small scale, in the 1920s.

But in most families, winemaking skipped a generation. From the 1940s to the 1970s, few were making wine. Many of Côte Rôtie’s families let their best, yet hardest-to-cultivate, vineyards go fallow, in favor of more lucrative work in the cities. And for those who continued to farm, it was both easier and more rewarding to grow vegetables and fruits, especially apricots.

By 1945 a kilo of apricots, at one franc, was worth more than twice as much as a kilo of Côte Rôtie grapes, and in 1949 the price for finished Côte Rôtie wine had slipped to just one franc per liter. As late as 1980, the legendary Marius Gentaz passed up the opportunity to buy the now famous La Turque vineyard reportedly because wine was not selling as well as his vegetables were.

A Murderer’s Row of Great Côte Rôtie Growers circa 1960-70s. From left Albert Dervieux, Marius Gentaz, unknown grower, Emile Champet and Robert Jasmin.

Rock-bottom was reached in the late 1950s. A huge 1956 storm devastated the vineyards and vine abandonment hit its peak. Those growers who chose to continue onward lost at least two vintages in the rebuilding efforts.

Yet, Côte Rôtie survived. And if you ask local growers today who was most responsible for its survival, most will give you two names: Vidal-Fleury and Guigal.

Joseph Vidal-Fleury had taken over his family’s firm in the 1920s, at about the same time the 14-year-old Etienne Guigal signed on to be his vineyard manager. For the next four decades, Vidal-Fleury was virtually the only game in town, buying up much of the growers’ Côte Rôtie production. He stood as a beacon of hope, even after Guigal left in 1946 to start his own company.

According to Jean-Paul Jamet, during the leanest years it was Vidal-Fleury “who permitted the continued existence of the appellation. Despite financial loss, the house supported the image of Côte Rôtie.” It was Joseph who told young growers: “You have to believe that Côte Rôtie has a huge capacity for quality ... Believe! You have to believe it!”

A Murderer’s Row of Great Côte Rôtie from the growers above. From left, wines from Albert Dervieux, Marius Gentaz, Emile Champet and Robert Jasmin.

But with virtually no one to work the vines and so little money to be made from them, the vineyards continued to dwindle. By the time Marcel Guigal joined his father in 1961, the amount of cultivated land was only 42 hectares. In fact, family friends advised Marcel to continue with his studies because winemaking in Côte Rôtie had no future. As he told us in an interview last year, they considered making wine in Côte Rôtie to be “madness, with winemakers destined for ruin.”

Against seemingly impossible odds, the situation slowly improved in the 1960s. Marcel proved to be every bit as skilled and tireless as his father. He worked with Albert Dervieux, president of the grower’s association, to save the vineyards from becoming residential land.

Guigal’s gradual success, as both grower and negociant, encouraged him to release of his first single-vineyard Côte Rôtie, La Mouline, in 1966 (coincidentally at the same time he acquired a U.S. importer, Classic Wines of Boston). Yet, other grape growers and wine producers found the going much tougher. Even the great Marius Gentaz grew both grapes and vegetables to survive.

Bottled wine still sold for a pittance. As René Rostaing told us during a recent visit, “until the ’70s there was no vigneron independant in Côte Rôtie who lived only by wine production. Everything was polyculture: they produced vegetables, fruit and grapes.” The first one to make it on wine alone was René’s father-in-law, Albert Dervieux.

That was the key to Côte Rôtie’s future: for landowners to be able to support a family solely by making wine. This not only assured that the best sites would be used for vineyards, it allowed growers to even increase their holdings. One of the first to do so was Dervieux, who began to organize each grape harvest by individual lieux-dit. And so Dervieux became one of the first growers to bottle Côte Rôties from individual terroirs as Guigal was doing.

Still, the growth in vineyards was slow. Even by the early 1980s, there were only 100 hectares of vines in Côte Rôtie—about the size of Ch. Lafite Rothschild. Much of the area was en friche—overgrown by trees and bushes—and the back-breaking work of clearing it, and planting new vines in the rocks, took years.

A photo of Marcel Guigal post-interview. By the time he joined his father in 1961, the amount of cultivated land was only 42 hectares. Friends counseled him to continue his studies fearing for the ruin of the family if he made wine in Côte Rôtie.

The pivotal decade for Côte Rôtie was the 1970s, with Guigal, and its single-cru La Mouline, showing the way. By the late 1970s, that wine had become the area’s first global icon, and the introduction of a second Guigal cru, La Landonne, in 1978, sealed the deal. The success of both wines not only elevated Guigal, it gave much-needed credibility to Côte Rôtie.

Meanwhile, a new growers’ syndicat, led by Albert Dervieux, was created to give shape to the area’s aspirations. And ambitious young foreign importers—like Kermit Lynch and the UK’s Robin Yapp—were beginning to knock on doors in Ampuis, in search of outstanding growers to represent. Côte Rôtie even got a boost from the local government, as Mayor Albert Gerin (himself an important grower) promoted the construction of roads up through Côtes Brune and Blonde, making it possible for the first time for mechanical equipment to reach Côte Rôtie’s most revered sites. Gerin also advocated an expansion of the appellation into areas that were easier to cultivate than the classic, rocky slopes.

Clear signs of Côte Rôtie’s rebirth appeared with the release of the 1976 vintage, an abundant year whose wines had the generosity of a hot, sunny vintage. As 1982 would six years later for the Bordelais, 1976 showed Côte Rôtie’s growers that there was money to be made, as they were able to charge increasingly higher prices in the face of strong demand. Within just three months of the vintage’s release, most of the producers were sold out at prices that were double the opening.

By the end of the decade, with all signs pointing to a brighter future, landowners planted aggressively. By the late 1970s, as many as 10 hectares of vines a year were being planted. And several of the next generation of vignerons took the unprecedented step of attending enology school, which set the stage for a leap in quality in the 1980s. Replanting also continued apace in the 1980s, aided by the use, for the first time ever, of machines to clear overgrowth and to break through the old stone terraces.

True worldwide recognition by the wine drinking public finally arrived with Robert Parker’s article in the January 1987 issue of Connoisseur Magazine. Parker referred to the 1985 Côte Rôties as “the most dramatic, intense wines I have tasted since my first tasting of 1982 Bordeaux reds.” He singled out the single-vineyard wines of Guigal and Rostaing for particularly high praise.

Combined with the stunning success of the Guigals—who three years earlier had come full circle by purchasing their former employers, Vidal-Fleury—the world had finally awakened to the greatness of Côte Rôtie.

But the forces that had finally brought prosperity to the appellation have also posed the greatest threat to Côte Rôtie’s unique character.

By the late 1980s, the door was suddenly wide open for growers to become domaine bottlers. And—as was happening in Barolo and Barbaresco at the very same time—many of these new producers were either fresh from enology school or hired consultants to tell them how to make their wine. And of course Guigal, with its more modern methods, served as a compelling role model.

Old barrels were replaced by new and single vineyard bottlings replaced assemblage cuvées. Grapes were picked at higher degrees of ripeness. And the traditional practice of whole-cluster fermentation (with the stems still in the mix) nearly vanished.

By the 1990s, a new, modern face of Côte Rôtie had emerged, and classic winemaking was longer the norm. Growers had convinced themselves that the surest way to high ratings—and high prices—was to change their style. It was, as Jean-Paul Jamet, told us: “super-ripe fruit, new oak, jackpot!”

This 1940s map by Larmat highlights some of the more renowned single vineyards like La Chatillone, Pommière, La Mouline, La Turque, La Garde and La Chevalière

Only a handful of staunch traditionalists resisted the siren’s call. Growers like Gentaz, Dervieux, Barge and Champet stuck to their guns, but at the risk of their wines either not being reviewed, receiving lower scores or simply not being understood, since their classic wines lacked the polish of new wood and an abundance of fruit.

Little was said or written about it at the time. Few journalists took sides, and, unlike in Piedmont, any animosity between the two sides was kept private.

So, while the modern-traditional debate brought renewed energy to Piedmont’s Old School, traditionally made Côte Rôties declined—in both number and visibility—as more modern versions, often made from the same plots of vines, emerged into the spotlight.

And while no one could dispute that the overall level of quality increased, it would be a mistake to think that something hadn’t been lost. For no matter how rich and satisfying the modern-styled wines are, they are not the same. There is something uniquely beautiful about classic Côte Rôties: their hallmark perfume of meat fat, truffles and underbrush, and their delicate grace on the palate, with a texture of pure velvet.

There is no question that the percentage of domaines working in the classic manner has fallen dramatically over the past 25 years. But survivors remain—growers dedicated to typicité, fiercely defending the idea that Côte Rôtie should taste like Côte Rôtie, not like Hermitage, and certainly not like new world Syrah.

And there is even reason to believe that in Côte Rôtie, as in Piedmont, the pendulum may be swinging back, as today’s winemakers rediscover the mastery of men like Marius Gentaz, Albert Dervieux, Emile and Joël Champet, Pierre and Gilles Barge, Joseph and Jean-Paul Jamet, René Rostaing and Robert Jasmin. These were the men responsible for making the 1970s, ’80s and ’90s Côte Rôtie’s Golden Age.

René and son Pierre Rostaing in the vineyard.

René Rostaing has made a life’s work of defending the idea that Côte Rôtie should taste like Côte Rôtie, not like Hermitage, and certainly not like new world Syrah.

In fact, he has been a beacon for those we’ve called the region’s “classicists.” These are the vignerons whose philosophies incorporate some new ideas while capturing the best of the region’s traditions. They make wines of purity and expression that are the essence of their region, village and vineyard.

A grower since 1971, Rostaing’s first vineyard acquisitions were a microscopic half acre each in Côte Blonde and in La Landonne on the Côte Brune.

The real breakthrough came when his father-in-law, Albert Dervieux retired in 1990, followed by his uncle Marius Gentaz three years later. Between these two legendary growers, Rostaing acquired over ten acres of very old vines in some of the appellation’s top sites.

“One of Côte Rôtie’s finest

classical producers.”

- John Gilman

René Rostaing has always been an independent thinker, whose winemaking is nonetheless deeply rooted in tradition, with an obsession for accurately expressing site, grape and vintage. In other words, he believes in making wines that could come from nowhere else but Côte Rôtie.

In the cellar, he uses only about 15% new wood on his Côte Rôties and is moving increasingly towards larger barrels. He employs roto-fermenters, but only so he can break up the must himself, not to shorten macerations. He prizes mature fruit, but rails against some of his neighbor’s much riper wines. In other words, this is the best of classic Côte Rôtie—brought into the modern age, but true to its origins.

Rostaing produces three Côte Rôties. His two vaunted single-lieu dit wines, Côte Blonde and La Landonne harken back to his beginning as a grower in 1971, which he purchased a half hectare each of La Landonne and Côte Blonde. His stake in Côte Blonde was increased with another half hectare from Dervieux, while his holdings in La Landonne were enhanced by an additional .3 hectare from Gentaz.

René Rostaing’s on the slopes of the iconic La Landonne vineyard.

La Landonne

La Landonne has historically been considered one of the great lieux-dits of Côte Rôtie. But it was not until 1978 that it became known to the larger wine-drinking world. In that year, not one but two towering cuvees began to be made from it by Guigal and Rostaing, each a wine of power and longevity, owing the site’s location in the northern sector.

Guigal’s version has been written about extensively, but Rostaing’s is every bit as worthy of attention. The vines are 100% Syrah (i.e., no Viognier), the oldest of which were planted in the 1920s and obtained from Marius Gentaz. The rest of the vines range in age from 10 to 70 years old. Vinification is, on the average, about two-thirds whole-cluster, with a 4- to 5-week maceration, involving pumping over and automatic cap punchings. On average only about 10-15% of the barrels he uses for La Landonne are new, and today two-thirds of the casks are large 550-liter barrels.

The Rostaing pavillon in the domaine's Côte Blonde holding

Côte Blonde

John Livingstone-Learmonth, who has studied Côte Rôtie intimately for four decades, writes that he expects “greater liason between Côte Rôtie and Burgundy than I do between Côte Rôtie and Hermitage.” And the term he chooses to describe Rostaing’s wines is Burgundian.

The Rostaing wine that best fits this description is his Côte Blonde, whose magical intensity without heaviness calls to mind the Côte de Nuits’ finest grands crus. In fact Rostaing himself told Livingstone-Learmonth that he regards the Côte Blonde lieu-dit as “the Chambertin of Côte Rôtie.”

His wine expresses this marvelous terroir with riveting purity. Inspired by his mentors, the legendary Marius Gentaz and Albert Dervieux, his judicious use of whole clusters and little new wood clearly articulates both soil and grape.

| Year | Description | Size | Notes | Avail/ Limit |

Price | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

1991

1991

|

1991 Rostaing Cote-Rotie Cote Blonde (ex-domaine) |

ST94 / RP92 |

6 | $695.00 | add | |

1991

1991

|

1991 Rostaing Cote-Rotie La Landonne |

RP94 / ST94+ |

2 | $595.00 | add |

We continue our series with another old-school producer, Domaine Champet.

If one were to search for today’s most purely traditional Côte Rôtie estate—the equivalent of Ch. Rayas or Henri Bonneau in Châteauneuf—it would be Champet. And the fact, that little here has changed over the past fifty years, makes this timeless domaine all the more magical.

The domaine is today ably run by Joël Champet and his sons Romain and Maxime. Joël has been a traditional icon in his own right for the past quarter century, but he would be the first to credit his father, Emile, for the philosophy that today sets Champet apart from virtually every other domaine in Côte Rôtie.

Everything is done with an utmost respect for tradition. His barrels are all old, and whole-cluster fermentation rules the day. In fact, if Joël wanted to destem, he couldn’t. He doesn’t even own a destemmer.

Joël’s vines are all in the great La Viallière lieu-dit. As late as the 1960s, La Viallière was almost completely covered with woods, but Joël’s father Emile took on the challenge of returning a prime part of this rugged terrain to vineyards.

It took Emile 35 years of working by hand to plant just three hectares—an extraordinary illustration of what Côte Rôtie’s true believers were willing to do to produce great wine, at a time when the extrinsic rewards for doing so were so small. But the result of Emile’s labor and vision is the iconic example of La Viallière, made ultra-transparent by the family’s old-school methods.

Joël at work in the cellar.

Viallière’s Guardian

La Viallière’s special qualities were first isolated by the revered single-vineyard Côte Rôtie pioneer Albert Dervieux. He knew that the Viallière terroir, an ideally southeast-facing slope of dark brown, fine mica-rich schist, can produce kaleidoscopically nuanced, broodingly powerful and very long-lived Côte Rôtie.

But Dervieux’ last vintage was in 1989, and his epic Viallières from the ’60s to the ’80s have become impossible to find. Luckily, in the Champets, we still have a traditional champion of Côte Rôtie making a cru wine from Viallière today.

Emile Champet enjoying the fruits of his labor. Photo courtesy of Yapp Brothers UK.

Pure Old School

Grower Bernard Burgaud recently said to us of Champet: “Emile was a total pioneer. He was the first to plant vines in the extraordinarily difficult conditions on the Viallière … in that parcel, he was all alone with his vines, surrounded by woods.”

Today Emile’s son Joël, and his grandsons Romain and Maxime are the guardians of this heroic effort. They’ve inherited Emile’s philosophy and “everything by hand” work ethic. They've made only minor changes to the winemaking, tinkering with how hard they press the grapes, for example.

They still vinify with typically 100% whole-clusters, fermenting and macerating with the native yeasts for two to three weeks with frequent pumping over. The year and a half elévage takes place almost entirely in neutral barrels, primarily large demi-muids augmented by a substantial number of 600-liter foudres and a handful of piéces before the wine is bottled without fining or filtration.

As a result, the Champets are arguably the most traditional grower in Côte Rôtie today, with the third generation inspired by their experiences drinking their father’s and grandfather’s wines from vintages like 1978, 1983, and 1990.

“Stunning quality ... utterly true to the traditional style of Côte Rôtie.”

- John Gilman

Our Offer Direct from the Domaine

As we did for René Rostaing last month, we have assembled an unparalleled range of both young and old vintages with which to understand Champet’s enduring philosophy. But the highlights of the offer are two of Champet’s most recently released harvests—2013 and 2014—with each bottle having come directly from the domaine.

Both vintages are superb for Champet—yielding a classically full, beautifully textured and aromatically nuanced Côte Rôtie, with the capacity to age for two decades or more with ease.

And at less than $50 a bottle, they are an absolute bargain for traditionally made Côte Rôtie, especially considering that only one wine is made and in such small quantities.

It is a tremendous honor to be able to make the first major U.S. offer of this unique and historically important wine in decades.

| Year | Description | Size | Notes | Avail/ Limit |

Price | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

2016

2016

|

2016 Champet Cote-Rotie La Vialliere | JG94 | 6 | $75.00 | add | |

1995

1995

|

1995 Emile Champet Cote-Rotie 1.5 L | 1.5 L | 1 | $425.00 | add |

Jamet Côte Rôtie has long been revered by those who love Syrah of great nuance and ethereal balance.

If you’re looking for blockbuster Côte Rôtie brimming with new oak and extract, you should look elsewhere. But if perfume and texture’s your thing, Jamet Côte Rôties are among the planet’s greatest wine experiences.

Change is on the horizon, however. If you follow the Northern Rhône closely, you may have heard that the brothers, Jean-Paul and Jean-Luc, split up a year or two ago. No formal announcement was made, and they have been reluctant to publicly discuss the change and what it may mean for the domaine. In particular, we know little about how the availability and make-up of the wines will be affected.

But it does appear that Jean-Paul—who has been the winemaker and, in our view, largely responsible for the domaine’s greatness—will remain in control. Still, it seems inevitable that the number and array of vineyards with which he has to work will be affected. And production may decline. We shall have to wait and see.

Despite having fruit from 17 of the most prestigious lieux-dits, the Jamets have resisted the temptation to produce multiple single crus, believing that the whole is greater than the sum of the parts.

The key to the fantastic complexity and balance of Jamet Côte Rôties has always been the family’s array of terroirs within the appellation. The domaine has its origins in 1950, when Joseph Jamet acquired .35 hectare in Côte Brune. For the first quarter century he was content to sell his wine to negociants for blending under their names. It was not until the 1976 vintage that the first Domaine Jamet wine appeared. That was the year his son Jean-Paul joined him.

A defining characteristic of the domaine’s wine then—and now—is that it has always been a single cuvée, skillfully blended from lieux-dits throughout Côte Rôtie. To this day, despite owning parcels in many of the most prestigious climats of Côte Rôtie, the Jamets have resisted the temptation to produce multiple single crus, believing that the whole is greater than the sum of the parts.

As Jean-Paul told John Livingstone-Learmonth, “We have 25 plots spread across 17 lieux-dits.” Every year, he carefully selects from these sites to craft a highly nuanced wine of haunting perfume, silky texture, elegance and finesse.

With his brother, Jean-Paul has had more than 30 years of experience working Côte Rôtie’s slopes. He has strong opinions on what influences the character of the wines from these different locations. For him, the nature of the soil is what matters most, followed by altitude.

The majority of the family’s lieux-dits are on the Côte Brune, whose brown schist soils produce black fruited Syrah, with strong tannic structure and longevity. Just two Côte Blonde sites—rooted in granite—provide the less structured floral, red fruit character that balances the Brune fruit so well.

And, just as the two Côtes complement each other, so do the varying altitudes—the wine from the high, cooler and windier sites leavening the rich, structured juice from the middle of the slopes.

“Year after year Jamet is the essence of

Côte Rôtie ...”

Yet, while this expertly tended palette of terroirs is the envy of many Côte Rôtie growers, Jean-Paul doesn’t necessarily use all of these sites for the flagship wine in a given year.

Rather, he strives “to find the best balance in the conditions of the vintage”; if a particular cuvée, regardless of how fine it is, would upset this balance, it is left out. As a result, year after year Jamet is the essence of Côte Rôtie, a wine of seductive texture and astonishing perfume.

His approach to making this wine is “classicist”—a term we would also apply to René Rostaing, Bernard Burgaud and Gilles Barge. Jean-Paul uses modern methods where they are of benefit, but he fiercely defends the idea that Côte Rôtie should taste like Côte Rôtie. For him, this means using mostly whole clusters for the primary fermentation in stainless steel which lasts about three weeks. It also means aging the wine in pieces and demi-muids—only 20% of which are new—for about two years.

Modest and philosophical, Jean-Paul works from a perspective born of experience. He’s learned to work simply, without unnecessary manipulations. “Why make it complicated when it can be simple?” was something he said repeatedly when we spoke to him a couple of years ago. His simple approach, and his instincts, allow him to find the essence of his many terroirs and then combine them in a strikingly clear portrait of Côte Rôtie and the vintage.

Any lots not used in the Côte Rôtie find a home in the family’s stunning Côtes du Rhône, a blend of declassified Côte Rôtie and the fruit from sites just outside the appellation.

With only about 150 cases made per vintage, Jamet's Côte Brune has emerged as one of the iconic collectibles of the Northern Rhône.

Of course, there is one other Côte Rôtie from the domaine: the painfully rare, single-vineyard Côte Brune bottling from father Joseph Jamet’s original tiny plot of 65-year-old vines. The Côte Brune is made just like the classique, but there is a slightly higher (33%) percentage of new barrels.

“In style it resembles another of the great Côte Rôties of the past, the Côte Brune of Marius Gentaz-Dervieux”, writes Livingstone-Learmonth. With darker fruit tone than the classique and great depth and structure, this is one of the great modern-day Côte Rôties.

We’re not sure the first vintage of Côte Brune; the earliest to pass through our hands was 1985. For decades this wine wasn’t directly imported into the United States, and even in Europe the existence of a second Côte Rôtie from Jamet was hardly known. In fact, merchants habitually mixed cases of Côte Brune and Côte Rôtie in their inventories. In the early years of our company—before Côte Brune became known and coveted—one of our favorite sports was opening the cases of newly arrived Jamet to see which wine we’d received!

Of course, everything is different today. The Brune is carefully allocated, and once it hits the market it sells for two to three times the price of Jamet’s regular Côte Rôtie. With only about 150 cases made per vintage, it has emerged as one of the iconic collectibles of the Northern Rhône.

| Year | Description | Size | Notes | Avail/ Limit |

Price | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

1989

1989

|

1989 Jean-Paul Jamet Cote-Rotie |

ST92 / JG93 |

1 | $1,750.00 | add | |

2006

2006

|

2006 Jean-Paul Jamet Cote-Rotie |

JLL**** / IWC93 / JG92+ |

2 | $295.00 | add | |

2012

2012

|

2012 Jean-Paul Jamet Cote-Rotie 1.5 L | 1.5 L |

JR94 / JD96 Read Notes |

3 | $499.00 | add |

2013

2013

|

2013 Jean-Paul Jamet Cote-Rotie 1.5 L | 1.5 L |

JR94 / JROB17.5+ |

6 | $435.00 | add |

2016

2016

|

2016 Jean-Paul Jamet Cote-Rotie |

JR96 / DEC97 |

10 | $199.95 | add | |

2016

2016

|

2016 Jean-Paul Jamet Cote-Rotie 375 mL | 375 mL |

JR95-97 / DEC97 |

6 | $99.95 | add |

2016

2016

|

2016 Jean-Paul Jamet Cote-Rotie 1.5 L | 1.5 L |

JR95-97 / DEC97 |

2 | $450.00 | add |

2015

2015

|

2015 Jean-Paul Jamet Cote-Rotie Cote-Brune |

JD98-100 / JLL6* / WA99 |

2 | $795.00 | add | |

2018

2018

|

2018 Jean-Paul Jamet Cote-Rotie La Landonne | 1 | $795.00 | add | ||

2019

2019

|

2019 Jean-Paul Jamet Cote-Rotie La Landonne | 1 | $795.00 | add |

Three generations of Jasmin. From left Alexandre, Robert and Georges Jasmin. Photo courtesy of Yapp Bros. UK

For more than a century, Domaine Jasmin has been a touchstone for those who prize Côte Rôtie that is full of finesse.

The domaine’s philosophy has been handed down through four generations. Even today, Jasmin is one of the few remaining producers to make only one Côte Rôtie—a blend of fruit from the domaine’s eight lieux-dits. It always including a small amount of Viognier, and it deftly marries the elegance from such granitic sites as Côteaux de Tupin and Côte Blonde, with the schist-derived power of 1920s Sérine vines in the Brune sector’s Moutonnes and Côte Baudin.

“A domaine whose wines hold great refinement ... Burgundian.”

- John Livingstone-Learmonth

A very early pioneer of grower-bottling, the domaine’s origins can be traced back to the arrival in Ampuis of Alexandre Jasmin from the Champagne region near the end of the 19th century. Alexandre came to work as chef at the Château d’Ampuis and, taking a strong interest in the local wine, soon purchased the adjacent vineyard in what is today the Les Moutonnes lieu-dit.

He soon began bottling his own production and presented his wine at the 1909 Concours Agricole in Paris, where it won medals. But while the domaine’s wines were sought after from the start, it was Alexandre’s son Georges, followed by Robert, who made Jasmin into one of Côte Rôtie’s great dynasties.

Robert and Georges Jasmin in the vineyard. Photo courtesy of Yapp Bros. UK

Georges took charge of the domaine in 1935, and his name is revered to this day by such greats as René Rostaing and Jean-Paul Jamet for his perseverance through the hard times of World War II and the 1950s.

His son Robert joined him in 1960, and father and son worked together until Georges’ half-century career came to an end with his passing at age 83 in 1987. Robert continued to build on the domaine’s great reputation, while changing nothing; as he told Rhone Renaissance author Remington Norman, “I do things just as grandfather did them.”

Not only did Robert resist the trend towards individual lieu-dit bottlings. He also resisted the trend of destemming. But, finally, in 1996, he relented and bought a destemmer. Prior to that, the fruit was always given a lengthy whole-cluster fermentation with the submerged cap held in place by planks. Aging was mostly in neutral pièce and demi-muid. The percentage of Viognier in the blend was a relatively high 5-6%, contributing to its penetrating perfume and delicacy.

Robert Jasmin. Photo courtesy of Alain Junguenet.

While hunting in 1999, Robert Jasmin was hit by a car and killed. His son Patrick was thrown into being the winemaker, and with little preparation, he miraculously produced a fine 1999 Côte Rôtie. Little has changed since then. Patrick continues to make his Côte Rôtie much as his father did after 1996. In other words, there is still a submerged cap, and the percentage of new barrels is relatively low, but the crop is 100% destemmed.

Finishing at an astonishingly classic 12.3% alcohol, Patrick’s 2012 Côte Rôtie is beautiful—possibly his finest Côte Rôtie since his very difficult 1999. After more than a decade of dwelling in his father’s shadow, he seems finally to be creating his own persona—making Côte Rôties that approach the quality of those made by his father and grandfather between the 1970s and 1990s.

| Year | Description | Size | Notes | Avail/ Limit |

Price | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

1994

1994

|

1994 Jasmin Cote-Rotie (Northumberland Country House Cellar; Lightly Bin Soiled Label) 1.5 L | 1.5 L | 1 | $595.00 | add |

Today, the world is awash in single-vineyard wines, and—let’s be honest—many would be put to better use as part of a blend. At fault is either a mediocre site or a winemaker whose methods aren’t transparent enough to bring the vineyard’s characteristic into sharp focus.

But when the site is right, and the winemaker knows what he or she is doing, the results can be magical. And one of our favorite domaines for getting it right is that of the Barge family, whose wines today are second to none as expression of both site and tradition.

Born to a family who’d been growing grapes since 1860, Jules Barge became the first in Côte Rôtie to sell domaine-bottled wines in 1929. His long career ended in the early 1970s, when he handed the baton to his son Pierre. As was typical for the times, both men made only one classique Côte Rôtie—a mixture of wine from Côte Brune and Côte Blonde, but with an emphasis on the former.

Innovation within Tradition

But in the 1979, Gilles Barge joined his father, inspired by the commercial success of his father’s great 1976 Côte Rôtie. He had already attended enology school—the first son of Ampuis to do so—and he had worked for a wine merchant in Ampuis for a few years. It was the perfect preparation for a skillful innovator: a young man steeped in his family’s traditional ideals, but with technical training and the experience of the marketplace.

From the time he joined his father until he took over in 1994, Gilles had the time (and intelligence) to chart the domaine’s future. He saw it as essentially traditionalist, with a heavy emphasis on whole-cluster fermentation and the use of mostly neutral, old barrels, especially demi-muids, for aging.

But Gilles has also saw opportunities to improve on the Old School’s ways. He reduced the use of sulfur (long before it became fashionable to do so) and he eliminated fining and filtration. He even conceived a way to continue practicing classic submerged cap fermentation in a temperature-controlled tank.

And perhaps most importantly, he reorganized the domaine’s wines, creating two highly expressive and unique single-vineyard cuvées, plus a blended wine that in itself is a masterpiece of typicity.

A look into the cellars at Domaine Barge.

Côte Brune

Arguably Gilles’ greatest wine is his Côte Brune, from vines 40 to 60 years of age planted in the brown schist soils of Côte Brune’s steep upper slope. These vines once provided the backbone for Jules’ and Pierre’s Côte Rôtie classique, but when Gilles took over the domaine from his father in 1994, he immediately separated out the best lots of Brune for its own cuvée.

Today, as it has been over the past two decades, it is as pure an expression as you’ll find of Côte Brune’s power. Only about 400 cases are made each vintage.

Le Combard

Nearly a quarter century after the first vintage of Côte Brune, Gilles created the domaine’s second single-vineyard wine: Le Combard, from a very steep, full-south facing lieux-dit at the southernmost part of the village of Ampuis.

Despite having soil that’s both extraordinary and unique in the appellation, it had been abandoned since World War I. Gilles often hiked Le Combard as a boy, but it wasn’t until he began making wine that he discovered how special this terroir is. He also hadn’t appreciated how carefully the ancients had thought out and planted this very challenging site.

The site is extremely steep and covered in glacially deposited large pebbles—something common to Châteauneuf but unheard of in Côte Rôtie. The volcanic subsoil is also unique to the appellation. It took two decades of unbelievably difficult labor, rebuilding the terraces and putting in a monorail to access the nearly vertical upper slope.

First bottled in 2009, Le Combard’s terroir produces a particularly savory peppery quality which marries beautifully with the floral character of its 8% Viognier. The result is an intensely aromatic Côte Rôtie that’s unlike any other.

Cuvée du Plessy

Gilles’ blended Côte Rôtie, Cuvée du Plessy, came out of a collaboration he began in 1978 with a neighbor, Joseph du Plessy. Scion of the pioneering domaine-bottling du Plessy family, he had vines in the Côte Blonde lieu-dit that were planted in the 1940s. From 1979 until 1994, Gilles vinified and bottle this fruit on its own, and the wine earned a loyal following as a beautiful expression of Côte Blonde finesse. In fact, in 1982, when Marius Gentaz’s UK importer asked for more Côte Rôtie, Gentaz pointed him Barge’s way, specifically recommending the cuvée made from the vines of M. du Plessy.

In 1994, upon taking charge of the domaine, Gilles believed he could put the du Plessy fruit to even better use, by creating an homage to traditional blended Côte Rôtie, in which the du Plessy fruit is the bedrock. This is essentially the Blonde counterpart to the Côte Brune wine, sourced primarily from such prime southern sector sites as Lancement, Boucharey and the ancient du Plessy vines from the Côte Blonde lieu-dit itself. Containing 5% Viognier, it is the essence of balance and refinement.

2012 Puts It All Together

Otherwise virtually unavailable in the US, we are delighted to give RWC clients the inside track on all three cuvées in the great 2012 vintage.

Classic examples of the Gilles Barge style, they are among the most beautiful, purest expressions of Côte Rôtie terroir made by anyone in the past thirty years.

You can purchase the wines individually below.But by the far the best deal is our 6-bottle 2012 Terroir Pack, which offers a savings of nearly $75. With two bottles each of Côte Brune, Cuvée de Plessy and Le Combard, it will give you a quick education in Barge’s greatness at an unbelievably low price.

2012 Barge Côte Rôtie

Terroir Pack

Includes two bottles each of Côte Brune,

Cuvée de Plessy and Le Combard

$325 6-pack

Also available individually

2012 Côte Rôtie Côte Brune $74.95 btl

John Gilman, View from the Cellar 94+ “The 2012 Côte Brune from Gilles and Julien Barge is a great young example of Côte-Rôtie, offering up a more reserved and deeper aromatic profile than either of the estate’s other two bottlings in this vintage. The first class nose offers up a classic blend of cassis, dark berry, black olive, venison, beautifully complex minerality, still a notable touch of stems and a topnote of woodsmoke. On the palate the wine is deep, pure, full-bodied and nascently complex, with a rock solid core, outstanding transparency and superb cut and grip on the focused and ripely tannic finish. This is going to be one of the top examples of Côte-Rôtie from the 2012 vintage, but it will need more time in the cellar to show all of its layers of complexity. 2023-2060.”

John Livingstone-Learmonth **** “... dark colour. Broad, grilled aroma ... an inlay of dark red fruit ... smoke ... this is grounded, traditional Côte-Rôtie ... red meat droplets come through late on, a wine that keeps its foot down on the pedal. Has ways to go, trails to cross and cover.”

2012 Côte Rôtie Le Combard $64.95 btl

John Gilman, View from the Cellar 93 “… a very strong endorsement for the special quality of this terroir. The classic nose delivers a fine constellation of cassis, meaty tones, violets, a bit of bonfire, a superb base of soil, a touch of nutskin and a topnote of freshground pepper. On the palate the wine is deep, full-bodied and complex, with a fine core, tangy acids and excellent length and grip on the ripely tannic and very well-balanced finish. Superb juice. 2022-2060.”

John Livingstone-Learmonth ***(*) “... rather dark robe. There is a brooding depth in the nose, a close-knit mix of blackberry, smoke, floral traces; it is still stiff, upright. The palate starts softly, grows into a mineral casing, pursues a consecutive line with no halts en route. A compact package with a little ‘fire’ and tar in it for now ....”

2012 Côte Rôtie Cuvée du Plessy $59.95 btl

John Gilman, View from the Cellar 92+ “The 2012 vintage in Côte-Rôtie is absolutely gorgeous … and the Cuvée du Plessy is already quite accessible and polished on both the nose and palate. The complex bouquet wafts from the glass in a lovely blend of plummy fruit, violets, coffee, raw cocoa, a fine base of chalky Côte de Blonde soil tones, nutskin, plenty of smokiness and a topnote of spices from the whole clusters. On the palate the wine is deep, full-bodied and nicely plush on the attack, with a fine, core, a bit of suave tannin and lovely length and grip on the focused and very well-balanced finish. A lovely bottle that is still a few years away from truly blossoming, but is already getting pretty hard to resist. 2020-2045+.”

John Livingstone-Learmonth ****(*) “... dark, properly full robe. The nose expresses power from within, has a concentration of red stone fruit and cassis ... raspberry, is handsome. The palate has a Blonde sector nature via a wavy spread of strawberry fruit, liqueur plum, the fruiting ripe. Has an appealing and fat center, heart, and tasty richness ....”

New discoveries, rare bottles of extraordinary provenance, limited time offers delivered to your inbox weekly. Be the first to know.

Please Wait

Adding to Cart.

...Loading...

By clicking the retail or wholesale site button and/or using rarewineco.com you are choosing to accept our use of cookies to provide you the best possible web experience.