Which site would you like to visit?

By clicking the retail or wholesale site button and/or using rarewineco.com you are choosing to accept our use of cookies to provide you the best possible web experience.

August 11, 2013

RWC talks with René Rostaing about winemaking in Côte Rôtie, both now and during the time of his legendary uncle, Marius Gentaz, and father in-law, Albert Dervieux.

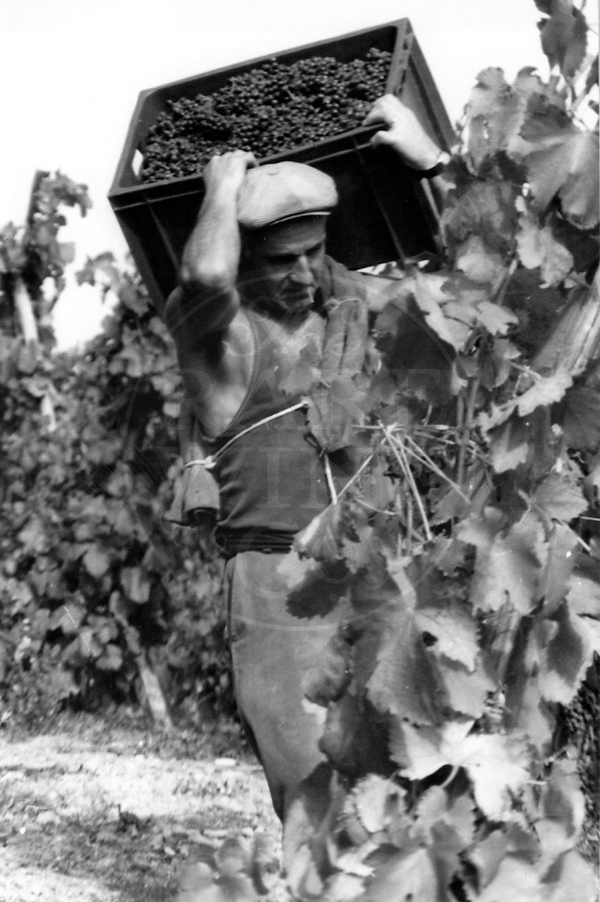

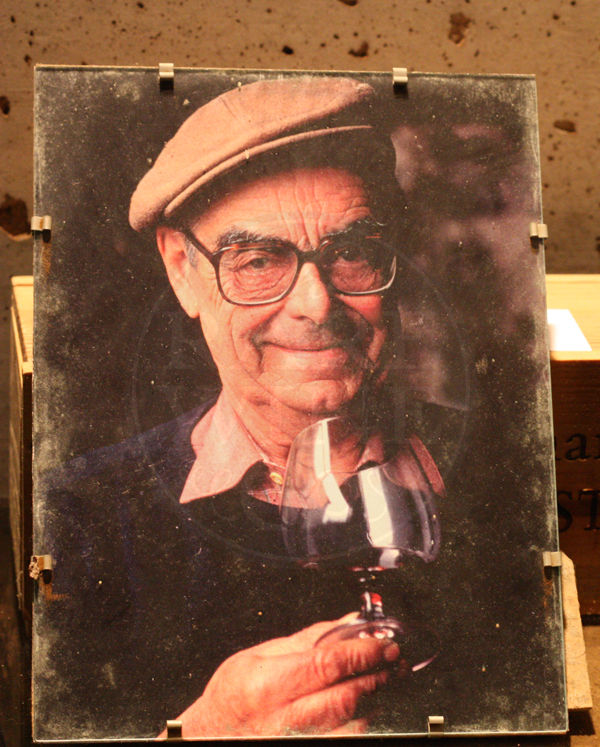

René Rostaing has been a pivotal figure in Côte Rôtie over the past forty years. He became a winemaker in 1971 with a scant half acre each of Côte Blonde and La Landonne. For the next two decades he established a reputation as one of Côte Rôtie’s finest winemakers in the traditional vein, his wines resembling those of his uncle Marius Gentaz and his father-in-law Albert Dervieux (each pictured to the right).

Then between 1990 and 1993, Dervieux and Gentaz retired, turning over their priceless vineyards to René. And so René Rostaing went from being a grower whose reputation was greater than his output to proprietor of one of the great domaines of the Northern Rhone, with more than 15 acres in some of the top lieux-dits of Côtie-Rôtie, including not only Côte Blonde and La Landonne, but also Côte Brune, La Garde, Fontgent and Vialliere.

RWC talks with René Rostaing about winemaking in Côte Rôtie, both now and during the time of his legendary uncle, Marius Gentaz, and father in-law, Albert Dervieux.

Throughout this process, René has remained true to Côte Rôtie’s most noble winemaking traditions, but he has also has proven to be fiercely independent. So long as he is making wines of which he can proud, it seems to matter little whether he is inside, or outside of, the winemaking mainstream. And he has been known to speak his mind freely, which made our opportunity to talk with him in his cellar, in April 2013, particularly compelling. Here are the results of that conversation.

RWC

Please tell us about 2010.

René Rostaing

A great vintage: “etendue,” elegant, not heavy. A vintage that improved, magnified, brought out the best of the terroirs.

RWC

Was the harvest small?

René Rostaing

In 2010 we lost about 20%. That’s fine, it’s not much. It was much worse in 2012. We lost about 30-35%, but in Burgundy they lost 70%. It was a catastrophe.

RWC

But wasn’t production even further reduced in the Côte Blonde in 2010?

René Rostaing

Yes, very.

RWC

Why?

René Rostaing

There was a small harvest of Côte Blonde, that’s all. That’s how nature works.

RWC

Was it frost?

René Rostaing

No, no, no there was no frost, but there were few grapes. That’s how it works. [he laughs]

RWC

Can we talk about the wine culture in the Rhône Valley? Some people say that in the past there wasn’t as much of a wine culture here as in Burgundy, for example. Do you agree with them?

René Rostaing

No, not completely. It is true that there is less of a wine culture here, as the vineyards are much smaller than in they are in Burgundy. Here, until the ’70s, there was no one in Ampuis [the town beneath Côte Rôtie] who lived only by wine production. Everything was polyculture, they produced vegetables, fruit, and grapes. While in Burgundy, in the ’70s, some growers already lived only on wine production.

But wine was a very old tradition in Côte Rôtie. It included a good knowledge of the different terroirs, and they knew each parcel and appreciated each parcel for its difference and for its quality. It was on a smaller scale, but a true “wine culture” was there.

If there hadn't been, it would be impossible to have Côte Rôtie as it is today. It didn't come out of nowhere, all of a sudden, created spontaneously. It’s not possible ... at least not in France. [laughter from everyone]

RWC

And do you think that is the same thing in Cornas also?

René Rostaing

Yes, absolutely! It is very similar and I can say that we both have many similarities with Burgundy, with the same knowledge of lieux-dits. It isthe same approach. It is a culture that is less obvious because there were other things that hid it. But it was there.

RWC

When Dervieux-Thaize and Gentaz started, did they sell their grapes?

René Rostaing

My wife’s grandfather Jean Dervieux only sold his wine in bottle.

RWC

In Lyon?

René Rostaing

Of course, in Lyon and even in England I think. And my wife’s father, Albert Dervieux, when he started, he was bottling his own wine. And Marius Gentaz always sold wine in bottle.

RWC

We spoke with someone who said that the great negociants like Vidal-Fleurie were very good for the region, which is different from what some people think.

René Rostaing

Yes I agree. Because in the beginning there were few vignerons who were making bottled wine. There were five: Jean Dervieux, the grandfather Barge, the grandfather Jasmin, the grandfather Duplessis and someone who no longer exists, André Drevon.

But, yes, there was a large dependence on negociants at that time. People here were not well-organized to sell. But little by little, they learned and gained knowledge about the international market. A long time ago there were only five winemakers who were bottling their own wine, and now we are forty.

RWC

We’ve also heard that Albert Dervieux and Marius Gentaz inspired people.

René Rostaing

Yes, I think so. They were the first to consistently bottle their own wine: the first conquerors of an export market. I think that at that time the quality of their vines and the quality of their wines was among the best. So, they were an example. Absolutely, they inspired, I agree.

RWC

And it's clear that they worked in a specific way. How did they find their way of working?

René Rostaing

They didn’t always chase perfection. Rather, they worked like their fathers and their grandfathers had worked: in a way that was rustic and empirical, and they were successful in making some really marvelous cuvées.

RWC

We've heard that Marius Gentaz was very precise as a grower.

René Rostaing

Yes. Meticulous. And then he had only 3 parcels, he had 1.2 hectares. One parcel in La Landonne. One parcel in Côte Brune at the tower of Guigal. And one in the lieu-dit Vialliere. Superb. He only had very very old vines ... that helps make good wine.

RWC

And were these vines from his family?

René Rostaing

Yes, his father, his stepfather, his father-in-law.

RWC

When were the vines bought?

René Rostaing

Oh, the family had them for a very long time. It was always in the family.

RWC

You said that Côte Rôtie was a polyculture. So, at the time did Gentaz grow other things?

René Rostaing

He cultivated vegetables, lots of vegetables.

RWC

Really?

René Rostaing

He went to the market every Saturday to sell his vegetables to the people of Vienne. Of course, he was a gardener as well.

RWC

When he went to sell his vegetables, did he bring his wine bottles along, too? Could you get your wine and your vegetables at the same time?

René Rostaing

[Laughs] No, it’s not the same thing.

RWC

So, he was someone known to make good wine and great vegetables?

René Rostaing

Yes.

RWC

And did he have a great good reputation in the town in general?

René Rostaing

Yes, he was a simple man—very discreet, so people liked him because he didn't make too much noise. But, yes, he was perhaps a bit too discreet. [Laughs] People liked him, but they did not accord him an important place. My father-in-law, Albert Dervieux, had more importance in the village. He was, above all, a public man.

RWC

Oh, really?

René Rostaing

Yes, he was president of the wine growers/producers syndicate for 30 years.

Mrs. Rostaing

He often went to Avignon and Lyon for meetings with viticulturists; Marius always stayed with his vines.

RWC

And did the two share their ways of working with others?

René Rostaing

Oh, I think everyone in Ampuis knew how to work the vines in the same way. Of course, they shared a lot, but it was in a more casual, natural way. If they saw each other in the street, they would talk to each other about their work. Naturally, that’s how things were shared.

RWC

But it seems that things have changed. In the newest generation ofvignerons, who first decided to use new barrels?

René Rostaing

It wasn’t that long ago. It was the generation after me. I'm from the generation right after Albert and Marius. The next generation of boys, who are now between 35 and 50, is the one that caught the maladie Californie. One-hundred percent new wood. One hundred percent de-stemmed. Very extracted. Fortunately, these practices are starting to dissipate. There is now more awareness, a taking stock, I think. I hope, at least, that they want to return to the wine a more traditional idea and more terroir. Truer, simpler ... and much better.

RWC

That started in the 80s?

René Rostaing

Let me think for a moment. Yes. It started slowly in 1980 and it hit its peak between 1990 and 2000. It exploded.

RWC

But I've also heard it that Joseph Jamet started at the same time.

René Rostaing

Yes, he did start around that time.

RWC

And why did he take such a different route from the others?

René Rostaing

He had good vines. He remained more traditional, truer. He had the courage to go against the grain and it worked. I am in total agreement with him on that.

RWC

And the people like Champet and Jasmin?

René Rostaing

Jasmin had a great tradition. His family, his father, his grandfather made very good wine.

RWC

If you disagree with how another winemaker works, do you ever say anything?

René Rostaing

It is an intimately personal opinion. Everyone has their own way they like do it, using their own sense, based on the influences, and the requests of their clients. The client says to the grower: my market wants wine with wood, and so he might consider following him a little. It's an influence resulting from many different things.

One day I was tasting wine at the house of [a Northern Rhône grower who is very modern in outlook] and I ask him “Are you ashamed of your terroir?” And he asked with surprise “Why?” And I responded, “because why would you hide it behind so much wood!”

He’s now changed a little bit, but I'm not sure he thinks that I was right. He thinks that he's right maybe. I don't know.

RWC

So, one is influenced by critics, by customers, by oneself. We’ve also heard that there has been an influence from consultants.

René Rostaing

Of course, there were several consulting oenologists who had an influence. But every winemaker has his own personality, his own work habits, his tastes, his familial tradition. You can’t really say that there is a general external influence. It is the result of the history that is intimate and unique to each person …. [pausing] … and his own individual reflection.

RWC

We spoke a little about Côte Rôtie but also that at Cornas there is Noël Verset and also August Clape. When you think about Clape, what do you think? In general, are there a couple of words that define the story according to you?

René Rostaing

You ask me my opinion, but I'm not from that terroir. I don't have all the elements at hand to judge Cornas. I have very precise and confident opinions concerning Côte Rôtie, because I know what I am talking about. But in Cornas, Clape has the reputation of being a great traditionalist. That's all. I know what you know, I don't know more.

RWC

And Albert Dervieux. What is his reputation?

Mrs. Rostaing (Dervieux’s daughter)

Generous. He loved making contact with others through his wines, like Bocuse and Troisgros, and others. He was very public. He liked having relationships but I can say that, for 20 years, he made some superb wine. From 1970 to 1990, he was at the top. Really, truly great.

RWC

Did his wines always have a great reputation in restaurants? We’ve seen photos of him with Paul Bocuse, with Troisgros, and it was clear that they loved the wines

René Rostaing

Yes, because Albert was probably the first to be 100% a vigneron. And it wasn't a choice. There had been expropriation of the land where he grew fruits and vegetables. He was given money. He had no more land for vegetables, so he reinvested in vineyards. That is the reason why Albert was the first to be 100% viticulture and to have a relatively significant volume. He was the only one to make a significant number of bottles, he was syndicate president, and he maintained good contacts—he knew Bocuse, etc. It was a little bit of all of those things that made him successful with restaurateurs.

RWC

And then, as he was the first, did others quickly followed in his footsteps?

René Rostaing

Yes, I think so. As soon as Albert was the first to become 100% a vigneron, and as the sales and prices of Côte-Rôtie increased, it became more and more interesting. It was a good [In English] “job!” So the youth [of Ampuis] re-bought and replanted vines. And that started happening in the ’70s.

RWC

And the role of Guigal at that time? Did he play an important role

René Rostaing

Yes, but the negociants have always had an important role. It is often said in France that in order for a wine region to be successful, there needs to be a strong negociant. And we have a strong negociant with Guigal here.

Mrs. Rostaing

And Etienne Guigal worked at my grandfather’s.

RWC

Really? He worked for Jean Dervieux?

Mrs. Rostaing

Yes, for a few years.

RWC

And so he learned how to make wine?

Mrs. Rostaing

And how to work in the vineyards, from Jean.

René Rostaing

And he also worked at Vidal-Fleurie … and then he bought the boss!

RWC

I have some questions about the terroir of Côte Rôtie, Côte Blonde, Côte Brune.

René Rostaing

I am quickly going to correct a common misunderstanding: that Côte Rôtie is divided in two, half Côte Blonde on one side, half Côte Brune on the other. That way of thinking is the result of a legend from before the French Revolution, from before 1089.

There was a Lord at the Château d'Ampuis. There is a legend that when he shared his vines, he gave to his brunette daughter the vines that we call Côte Brune and to his blonde daughter Côte Blonde. But it is an oversimplification that it is 50% of each: that the land that is across from the church’s bell tower to the south is all Blonde and to the north is Brune.

The Côte Blonde and the Côte Brune are lieux-dits—like many other lieux-dits—and there are around fifty lieux-dits in Ampuis. Together, the Blonde and Brune represent only 3% of the appellation! It's an oversimplification to call it half Brune, half Blonde. It's simple, it's easy. But we must re-establish the truth!

RWC

Absolutely. And the lieux-dits: when did the notion of lieux-dits start developing?

René Rostaing

It developed in 1970 or ’75. I think that Albert Dervieux was the first, along with Guigal to have vinified wines by parcel.

RWC

And before that, how was it?

René Rostaing

Before it was “Les Ampuisés”. They didn't use lieux-dits. Often they were just selling wine in bulk, by the ton. So there was no interest in doing that. And I think ... Madame Dervieux who owned La Mouline, she called it La Côte Blonde. And Mr. Duplessis who is now no longer with us, who has no successors, had a Côte Brune label. But there were three or four, and they made only 3, 4 thousand bottles each, so it was very confidential … under the radar.

RWC

And this was in the ’70s?

René Rostaing

’50s ’60s ’70s. But this is an old story. These things existed on a very small, very reduced scale. So we didn't know about them. But it already existed.

RWC

It seems like your families continued to produce wine from the 1910s. How is it that they continued to produce wine through two World Wars and the Great Depression when it affected many people in a very serious manner? How much were they affected?

René Rostaing

Not too much at all, actually.

Mrs. Rostaing

They had a polyculture.

René Rostaing

And also those effects happened primarily in urban zones, in the cities, in industry, in commerce, in business in general where one can feel the crisis. But in the agricultural world, not so much.

RWC

And during the war?

René Rostaing

During the war it was difficult, but they still made wine all the same. It certainly sold less well, cheaply, and in bulk or in the cafés in Vienne. In the bistros we drank Côte Rôties sold to them in bulk, And after that, things changed [for the better]. But all the same, they got by well enough; it wasn't too bad. They lived simply.

RWC

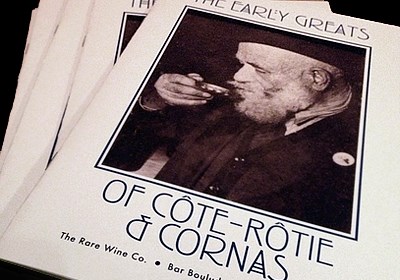

And what do you think about of the series of tastings our company is doing in New York: 5 winemakers, 5 terroirs, Noël Verset, August Clape, Marius Gentaz, Joseph Jamet, and Jasmin—around 15 vintage of each one. What do you think about that?

René Rostaing

15 vintages of three vignerons of Ampuis? Wow, [in English] “what a job!”

Mrs. Rostaing

You have more wine than us!

RWC

Would your parents have ever thought of a tasting in New York?

René Rostaing

No, never, that wasn't how things were done at the time.

RWC

And if they had heard about something like that, what would they have said?

René Rostaing

Oh, they would have said: “C’est formidable!” Because they thought everything was great. They had great personalities.

Mrs. Rostaing

For what reason or occasion are you holding these tastings?

RWC

The idea is to show that the wines of the Northern Rhône Valley are grand vins not only of France, but of the world.

Mrs. Rostaing

Have they been successful?

RWC

The response was incredible. We started with only one bottle of each vintage. But we decided that we needed to have more because we were going to have to refuse about forty people for each tasting.

René and Christiane Rostaing

Really!?! To use two bottles!

RWC

Yes and unfortunately some of these are the last bottles.

A question that I forgot: are there any lessons in particular that you learned from Albert and Marius?

Mrs. Rostaing

Actually, I would almost say it is the contrary.

René Rostaing

Me, I could not say that. Yes, I think your father taught me things [to Christiane, referring to her father, Albert Dervieux] about the vines, the cultivation of the vine, yes. But for wine, no. Because Marius and my father-in-law were very traditional, they only used old traditional methods. But I was from a different generation and I followed the methods of my generation. There had been some progress and some improvements.

RWC

In your opinion, what are these improvements?

René Rostaing

I know we became more attentive to yields. That's for sure. We learned from science the importance of hygiene. I am not saying we were doing things better, but we thought about it. While my uncle and father-in-law did things well, they didn’t know that their actions would have such importance. And then a few new ideas were brought out, like destemming. My stepfather and Marius had no idea what destemming was. They never did that. We had more modern materials, such as pneumatic presses, etc. Techniques evolved. I vinify in a rotofermenter, while Albert and Maurius vinified in a traditional cuvée made of concrete.

But evolution does not necessarily mean that things are better. A very simple example: for Christmas this year or last, I drank the last bottle of Côte Rôtie from my grandfather. Côte Blonde 1947. You were not yet born. 1947. The wine was extraordinary. Young, powerful, perfumed, flavorful, colored... incredible! Incredible! And my grandfather knew nothing about oenology … he didn't have any specific or complicated tools. And so, they made great wines. Sure that was a great vintage, 1947, but this was a wine that aged sixty-four years without a problem! Do you realize?

So I say modern technique is not necessarily a systematic improvement. It makes work easier, and perhaps it prevents certain problems that arise during difficult vintages. I think it is there to avoid [in English] a “crash”—the big problems that can happen if a year is difficult. But, you know, modernism, too much modernism, can suffocate or hide a great, sublime vintage. Modernism—too much use of techniques like heating and re-cooling the wines, adding yeast and enzymes, too much new wood—all that can make a great vintage lose or at least hide its purity of expression.

RWC

But there are some who may consider René Rostaing modern. Do you consider yourself a modernist, traditionalist, or something between the two?

René Rostaing

I ask if this distinction between modernist and traditionalist is a good idea or more of a false problem.

RWC

That’s a perfect answer.

René Rostaing

It is a political answer. Diplomatic. But I really think that, it is not a real distinction, because we all have traditional aspects and we all have modern aspects. And it is a mix of all that, it is not all one or the other. It's not true. A man is more complex than that.

RWC

Thankfully.

René Rostaing

There you go. And of course, journalists, writers have the tendency to define in an oversimplified, broad way the winemakers … In general, a journalist needs to find strong ideas to have an article, a real [in English] “scoop,” that pleases everyone, that attracts the reader. And there is then the tendency to fall into stereotypes, a way of defining that is too marked.

RWC

In Piemonte, rotofermenters are used for making the most modern of wines with a short maceration. How are you using yours?

René Rostaing

I have been doing a a twenty-year experiment, and I find that with these [rotofermenter] cuvées, using them in a moderate way, you can obtain both a perfect extraction and finesse.

RWC

How many days do you macerate?

René Rostaing

Two weeks. Two weeks of fermentation, two weeks of maceration.

RWC

That’s the opposite of Piemonte, where they use them to physically beat up the must and shorten the maceration to something like two or three days.

René Rostaing

[gasps]

RWC

That can make a black Nebbiolo.

René Rostaing

Yes, so they turn and turn for three days.

RWC

Here, how many times do you turn the rotofermenter a day?

René Rostaing

Me? Twice a day and three turns each time. That makes six turns a day, but very slow, gently. But that’s during the period when fermentation is very active. When the fermentation lowers, when the curve lowers, I do it much less. And when I am macerating, I do it once every two or three days.

It is important to extract, but one should not club or beat up the wine. One wants to keep the finesse. I vinify with an old, traditional mindset and spirit, but with modern materials.

Mrs. Rostaing

Even with destemming.

René Rostaing

Yes, in the Ampodium cuvée I only destem 30 or 40%. In Landonne and Blonde, 10%. And sometimes, zero: no destemming. I am not systematic. I make the wine that I like.

And that’s the “scoop.” Because there are things to learn everywhere. In the old tradition and in the modern one. I am sure of it. And one has to adapt it to his own terroir. What is true in Côte Rotie is not true in Hermitage and even less so in Piedmont. One needs to reflect on one’s level and try to pull the most out of what he has.

René Rostaing

Marius Gentaz

Marius Gentaz

New discoveries, rare bottles of extraordinary provenance, limited time offers delivered to your inbox weekly. Be the first to know.

Please Wait

Adding to Cart.

...Loading...

By clicking the retail or wholesale site button and/or using rarewineco.com you are choosing to accept our use of cookies to provide you the best possible web experience.