Which site would you like to visit?

By clicking the retail or wholesale site button and/or using rarewineco.com you are choosing to accept our use of cookies to provide you the best possible web experience.

August 4, 2009 by Greg Dolgushkin

Having been given the honor of opening the 28 bottles for the Leacock Madeira Tasting (two bottles of each wine), it would be an understatement to say that I understood the importance of my task. The wines were all very rare and irreplaceable, and a few were of great historical significance as well.

I was charged not only with cleanly removing 28 ancient, and possibly crumbling, corks, I had to calibrate the amount of air that the wines were given, so that six days after opening they would show at or near their best.

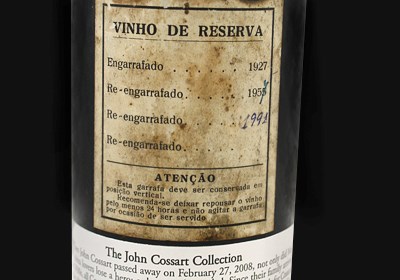

The wines had been in bottle a very long time—from 60 to 100 years—and every bottle, even when of the same wine, was a new experience. Unusually, most of these bottles had been binned on their sides, a risky practice as Madeira’s high acidity can destroy the cork, but in this case, it worked.

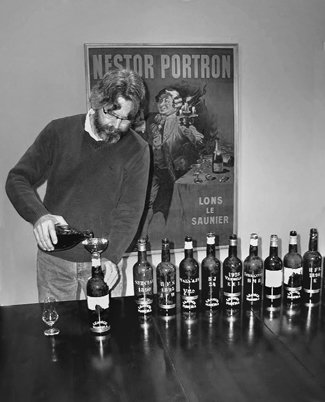

Greg Dolgushkin decanting the Leacock bottles in our Sonoma office.

The cork in the first bottle, the anonymously stenciled “A” (which we now believe to be an aguardente) came out intact, compacted, short, deeply stained and unbranded. The contents were expressive and fresh on both nose and palate: high-toned, nutty and very dry. The second bottle of “A” had a similar cork and much the same flavor/aromatic profile, but deeper on the nose and fuller and more viscous on the palate.

The 1934 Leacock “SJ” was another mystery—we know that SJ stands for São João, the Leacock’s own vineyard, but don’t know the grape varietal. This was the first problem cork, crumbly and difficult to extract; fortunately, the wine was sound: clean, delicate and high-toned. The second bottle was drier and more astringent, needing more aeration.

Both bottles of the Leacock Malvazia “VMA” had short, loose corks—the wine, understood to be very old was elegant, sweet and delicate on the palate with strong acidity. The first bottle was more reticent on the nose—not reduced but not very expressive on the nose, another candidate for longer aeration.

The next two, the 1896 HFS “E” and 1895 HFS “JPW”, presented more questions as the grapes used are unknown. Both had difficult corks, some loose and some crumbly, and the wines had clearly been in bottle for a very long time. The "E"was pungent and nutty with a buttery richness and an intriguing sweet and tangy finish.

The “JPW” corks were soaked and crumbly and both bottles needed air—the first was a bit musty, but sound in the glass while the second was quite volatile and pungent with raisin and cider notes. Surprisingly, the “JPW” bottles had yellow foil capsules imprinted with “João Pereira D’Oliveira”, suggesting they had passed through this house at some point, but why?

The cork in the first bottle of 1881 Leacock Terrantez was surprisingly short—I thought it had separated in the neck before seeing that it was intact—and the wine was quite pungent, with a fudge-like richness and telltale bitter note on the finish. The second bottle—with a cork twice as long—was even better, similar on nose and palate but far more expressive. This too was a wine that was unknown before the Christie’s auction.

The incredibly rare A.G. Pacheco was legendary to Madeira insiders, yet nothing but the name (probably of its grower) is known about it. The wine was excellent—sound, clean and delicate with a mineral pungency. The corks in the Pacheco were the most difficult in the range; they were not only crumbly, they adhered to the inside of the neck. Could these have been stored upright?

The famous 1868 “EBH” Very Old Bual—again with a yellow foil D’Oliveira capsule—was a brilliant example of how Bual transforms with age-pungently aromatic but ethereally fine and delicate. Both bottles showed beautifully upon opening.

The two bottles of 1845 Quinta da Paz were very different—the first a bit musty and reduced when first opened, although clean, if inexpressive, in the glass. The second was far more powerful, deeper and fuller on the palate with explosive aromatics of dried red plum and quinine.

The 1836 Lomelino Bastardo was fantastic—rich, sweet and powerful on the palate with high-toned lime blossom aromatics. Both bottles showed well, but as usual, one was more extroverted than the other.

Lastly, I had the privilege of opening the Borges “HMB” Terrantez, which though absent a vintage on the bottle, may well be the legendary 1862. Bottle #1 was a little reduced at first, but was buttery rich and powerful on the palate with the varietal’s trademark bitter finish. Bottle #2 was similar but more backward. But from the moment of opening, both showed the potential for true greatness.

These were the first, brief snapshots—my impression was that all of the wines were going to become a lot better with air, even those that were initially expressive. Now came the decanting. Though we were limited to 14 decanters, we poured the wines for Saturday’s tasting first, minus those already decanted for extra aeration, giving them a full day and then back into the rinsed bottles, freeing up the decanters for Sunday’s wines, with the process repeated as many times as we could prior to the tastings.

Once the wines had been poured through a double layer of cheesecloth, we had more evidence of lay-down storage, as almost all of the bottles were heavily crusted with sediment. The bottles were rinsed thoroughly with hot water until I saw no sediment flowing out and then left to dry inverted to make certain that all of the water drained out.

Some wines blossomed almost immediately in the decanters, while others remained stubbornly backward. And once the second set had been poured the bottle variation was even more apparent. Clearly the hand bottling combined with the quality of the corks and subsequent storage made each bottle a unique expression.

Provenance was undoubtedly a factor in how the wines behaved. While all of the Leacock Family’s bottles had ended up with William Leacock, a few surely passed through different hands and saw different conditions during their long stay in bottle. In each pair, the bottles had distinct personalities, while sharing the same character, like the differences between siblings raised in the same environment.

As I worked with the wines over several days, I began to make adjustments, moving the most reticent wines to magnum decanters to increase the aeration. It was exciting to witness the transformation in these wines, but in the end I believe that all of them could have benefited from even longer aeration.

As the week wore on, I became more and more aware of what a unique experience this was. The bottles were an amazing journey, a study of living wine filled with mystery, endless complexity and history providing a new perspective of what wine can be.

| Year | Description | Size | Notes | Avail/ Limit |

Price | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Please Call (415) 319-9000 for Availability | ||||||

New discoveries, rare bottles of extraordinary provenance, limited time offers delivered to your inbox weekly. Be the first to know.

Please Wait

Adding to Cart.

...Loading...

By clicking the retail or wholesale site button and/or using rarewineco.com you are choosing to accept our use of cookies to provide you the best possible web experience.